I recently ventured into territory that was thus far unchartered for me: mobile development. As my evening schedule became less and less pre-occupied with post-work work in support of the PyTorch 1.0 release, I noticed pockets of time I wanted to fill with an interesting side project that would teach me something new. The exact details of this project aren’t relevant to this post, but in short, it was an iOS app written in Swift that involved detecting bounding boxes for text in images. Since you asked, those images would usually contain food menus – of course, all my activities are usually in pursuit of or related to food.

As I concocted a plan of attack for this project I was faced with three major design decisions: what platform to target (iOS, Android or both); what framework to use (Swift/Java or React Native) and lastly whether to train my own machine learning algorithm and ship it to the device, or call into an off-the-shelf cloud API. Since all my devices have Apple logos on them the first was an easy choice. The second I pondered over for a little longer. I had wanted to learn Swift for some time, having heard much praise and much criticism of this relatively new language, and wanted to compare it to Rust and other new-ish languages. On the other hand, React Native sounded very exciting too, being an immensely popular framework developed by my “home team”, Facebook. I ultimately settled on Swift for the reasons I mentioned, and I think that was a fine decision. The last discussion point warranted more intensive investigation. I spent some time reviewing the latest literature and state-of-the-art in object character recognition (OCR) and while I did settle on a particular model and had my GPUs all warmed up and ready to flip some FLOPs, I finally decided that using the Google Cloud Vision API would save me a couple weeks of work with perfectly acceptable results. Their free tier also sufficiently covered my needs, so I called it a day and conceded that Google knows a thing or two about OCR too.

Now that you have all the background you were never interested in, let’s move on to the technical part of this post. I’ll begin by discussing the Google Cloud Vision API with a particular focus on OCR and show how to interact with it purely via cURL and the command line as an appetizer. I’ll then walk you through setting up photo capture in a basic Swift app, sending captured images to Google’s clouds and displaying the recognized text and bounding boxes that rain back down.

Using the Google Cloud Vision API

The Google Cloud Vision API is a set of API endpoints that provide various forms of image analysis as a service. Given an image, you can ask for the class of the object to be recognized, for reverse image search results, for unsafe content detection (e.g. nudity or violence) and – relevant to our use case – text recognition. What is convenient about the latter service is that it actually provides two kinds of results in one: you get bounding box coordinates of any text “groupings” (words, sentences, paragraphs) as well as the recognized text within each bounding box. This means you can display visual markers for each bounding box and then perform some action based on the detected text when a user interacts with a certain bounding box. This OCR service is free up to 1000 API calls per month at the time of this writing. Refer to the full pricing information to see where the price goes from there (it’s reasonable).

Allow me to leave you to the official guides on setting up Google Cloud and enabling the API. When you come back, you want to be in a position where the following command (taken from here) gives you a successful response:

$ curl -X POST \

-H "Authorization: Bearer "$(gcloud auth application-default print-access-token) \

-H "Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8" \

--data "{

'requests': [

{

'image': {

'source': {

'imageUri': 'gs://bucket-name-123/abbey_road.jpg'

}

},

'features': [

{

'type': 'TEXT_DETECTION'

}

]

}

]

}" "https://vision.googleapis.com/v1/images:annotate"

Let’s bisect the structure of this request a bit, since we’ll be sending similar ones in our app

later on. The request itself is an object, with a single key requests whose value is one or more

API requests in a list. Each request in turn contains an image, and specifies one or more services

we request for this image. The image can be supplied in various forms. Above, we specify a URI

pointing at a Google Cloud storage bucket. In our application, we’ll instead be embedding the entire

image as a base64 encoded string. One noteworthy detail about the features we request to be analyzed

is that we could swap TEXT_DETECTION for DOCUMENT_TEXT_DETECTION. TEXT_DETECTION uses a model

more optimized for text “in the wild”, such as street signs or food menus. DOCUMENT_TEXT_DETECTION

instead provides better results for very dense text as found in documents such as pages of a book.

Lastly, the API endpoint we target with this request is images:annotate to access the OCR service,

which we append to https://vision.googleapis.com/v1 to form the complete URL.

The full JSON response from the above cURL command is quite a lot to digest. To get a more succinct

overview, let’s beam up the following image (download it and save it to disk as test-image.png):

We’ll now employ the alternative mechanism of supplying the image payload: embedding a base64

encoded string of the image data. Unix systems conveniently have a base64 command into which we

can simply pipe the image to get the encoded string. We can even embed this into the cURL command:

$ curl -X POST \

-H "Authorization: Bearer "$(gcloud auth application-default print-access-token) \

-H "Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8" \

--data "{

'requests': [

{

'image': {

'content': '$(cat test-image.png | base64)'

},

'features': [

{

'type': 'TEXT_DETECTION'

}

]

}

]

}" "https://vision.googleapis.com/v1/images:annotate"

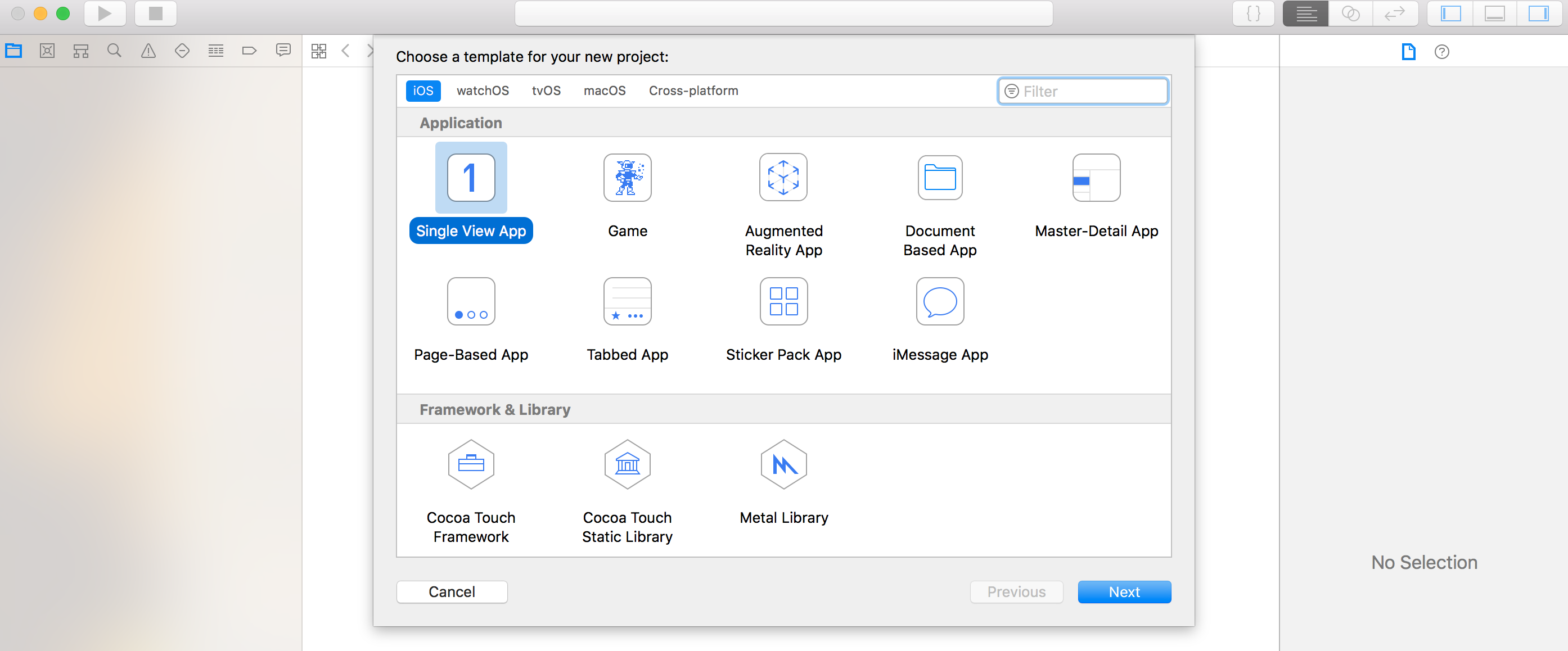

The response should look largely like the one below. I’ve omitted the fullTextAnnotation object

which has very fine grained annotations, down to individual characters. We’re more interested in the

textAnnotations objet, which provides annotations at the level of sentences and words:

{

"responses": [{

"textAnnotations": [{

"locale": "en",

"description": "Optical Character Recognition\n",

"boundingPoly": {

"vertices": [{

"x": 5,

"y": 18

},

{

"x": 372,

"y": 18

},

{

"x": 372,

"y": 44

},

{

"x": 5,

"y": 44

}

]

}

},

{

"description": "Optical",

"boundingPoly": {

"vertices": [{

"x": 5,

"y": 18

},

{

"x": 88,

"y": 18

},

{

"x": 88,

"y": 44

},

{

"x": 5,

"y": 44

}

]

}

},

{

"description": "Character",

"boundingPoly": {

"vertices": [{

"x": 99,

"y": 18

},

{

"x": 218,

"y": 18

},

{

"x": 218,

"y": 38

},

{

"x": 99,

"y": 38

}

]

}

},

{

"description": "Recognition",

"boundingPoly": {

"vertices": [{

"x": 227,

"y": 19

},

{

"x": 372,

"y": 19

},

{

"x": 372,

"y": 44

},

{

"x": 227,

"y": 44

}

]

}

}

],

"fullTextAnnotation": {}

}]

}

The textAnnotations section contains a list of objects for each detected sentence and word. In

each object, the description contains the recognized text and the boundingPoly describes a

polygon that encloses this text. The coordinates of this polygon are in pixels relative to the

origin (top left corner) of the image. When possible, the service will also return a locale to

indicate the language it believes the text to be. And that’s all there is to the response really,

although you can inspect the documentation for

AnnotateImageResponse

to get the full picture (without bounding boxes – ha). We’ll dive into developing the app next.

Building the Swift iOS Application

The next few paragraphs explore setting up a basic iOS app in Swift that has the ability to capture photos using the phone’s camera. Subsequently we will discuss making the API calls we just studied from within our app. The last step is to display the bounding boxes on the captured image. I’ll also hint at how to perform actions based on interactions with bounding boxes and their associated text.

The full code for this tutorial can be found in this repository if you want to follow along.

A Basic App

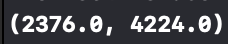

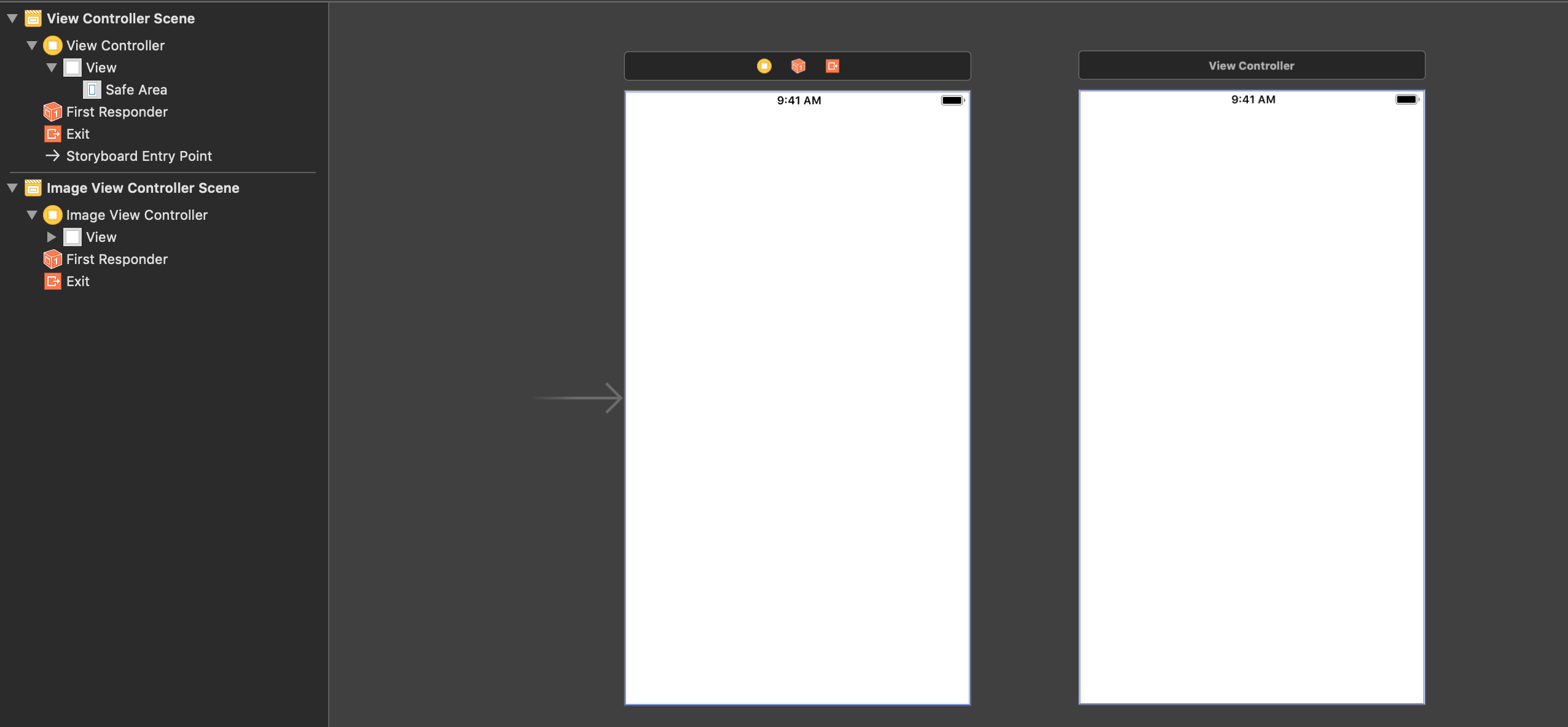

I assume you have some (minimal) prior experience with developing iOS apps with Swift and XCode, so I won’t cover the basic basics. If either of these are new to you, I found the Swift language guide and official tutorial on iOS development pretty good to get started. Let’s start by creating a new single view app project in XCode:

I chose GoogleCloudVisionOCRExample as the name for my project. Building the app and running it in

the Simulator should present you with a beautiful white screen filled with blissful nothingness:

Setting Up Basic Image Capture

Let’s continue by changing our most bare ViewController.swift to import AVFoundation, the kit

that exposes the relevant photo capture interface. We’ll begin by setting up a live photo preview in

our main ViewController. To reduce the number of screenshots in this post, I’ll do most of this

programatically. You can naturally use the InterfaceBuilder and connect the apropriate outlets to

the ViewController if you prefer a more visual approach. Also note that the XCode iOS simulator

does not have a camera, so you will need to connect a physical phone from here on. The

ViewController.swift that comes with the empty app should be populated as follows:

import UIKit

import AVFoundation

class ViewController: UIViewController {

var captureSession: AVCaptureSession!

override func viewDidLoad() {

super.viewDidLoad()

setupCamera()

}

override func viewDidAppear(_ animated: Bool) {

super.viewDidAppear(animated)

captureSession.startRunning()

}

override func viewWillDisappear(_ animated: Bool) {

captureSession.stopRunning()

}

private func setupCamera() {

let captureDevice = AVCaptureDevice.default(for: AVMediaType.video)

var input: AVCaptureDeviceInput

do {

input = try AVCaptureDeviceInput(device: captureDevice!)

} catch {

fatalError("Error configuring capture device: \(error)");

}

captureSession = AVCaptureSession()

captureSession.addInput(input)

// Setup the preview view.

let videoPreviewLayer = AVCaptureVideoPreviewLayer(session: captureSession)

videoPreviewLayer.videoGravity = AVLayerVideoGravity.resizeAspectFill

videoPreviewLayer.frame = view.layer.bounds

view.layer.addSublayer(videoPreviewLayer)

}

}

We first declare an AVCaptureSession that allows starting and stopping the video preview layer

displayed in the app. Upon viewDidLoad() we call setupCamera(), where we initialize this capture

session by supplying it an appropriate AVCaptureDevice, configured for video (or photo) input.

We also add a preview layer to our main view. When the viewDidAppear() we start the capture

session and stop it again in viewWillDisappear() if the view were to segue to a

different view controller.

Before we can run the app properly, we need to edit our Info.plist file to

enable permissions for accessing the camera device. Add a line like this:

If you now run the application, you should see a live preview of whatever the camera on your phone currently captures:

Next, we need to setup the flow for taking a picture. For this, we’ll add a

UITapGestureRecognizer to our ViewController. We can connect this tap

gesture recognizer to a custom handler function, inside which we’ll snap a

picture and process it further:

class ViewController: UIViewController {

var captureSession: AVCaptureSession!

var tapRecognizer: UITapGestureRecognizer! // NEW

override func viewDidLoad() {

super.viewDidLoad()

setupCamera()

setupTapRecognizer() // NEW

}

private func setupTapRecognizer() {

tapRecognizer = UITapGestureRecognizer(target: self, action: #selector(handleTap))

tapRecognizer?.numberOfTapsRequired = 1

tapRecognizer?.numberOfTouchesRequired = 1

view.addGestureRecognizer(tapRecognizer!)

}

@objc func handleTap(sender: UITapGestureRecognizer) {

if sender.state == .ended {

print("Tap!")

}

}

If you now run the app and tap on the screen once the live preview shows up, you

should see friendly "Tap!" exclamations in the XCode output terminal. Let’s

continue by acting on these taps beyond just printing a message in the terminal.

We need to add a new AVCapturePhotoOutput property to our ViewController and

a method to initialize this object, which we call in viewDidLoad() after

setupCamera():

class ViewController: UIViewController {

var captureSession: AVCaptureSession!

var tapRecognizer: UITapGestureRecognizer!

var capturePhotoOutput: AVCapturePhotoOutput! // NEW

override func viewDidLoad() {

super.viewDidLoad()

setupCamera()

setupTapRecognizer()

setupPhotoOutput() // NEW

}

private func setupPhotoOutput() {

capturePhotoOutput = AVCapturePhotoOutput()

capturePhotoOutput.isHighResolutionCaptureEnabled = true

captureSession.addOutput(capturePhotoOutput!)

}

Next, we extend our ViewController with the methods necessary to take a photo

and be an AVCapturePhotoCaptureDelegate. Add the following block of code just

below the main ViewController class definition inside ViewController.swift:

extension ViewController : AVCapturePhotoCaptureDelegate {

private func capturePhoto() {

let photoSettings = AVCapturePhotoSettings()

photoSettings.isAutoStillImageStabilizationEnabled = true

photoSettings.isHighResolutionPhotoEnabled = true

photoSettings.flashMode = .auto

capturePhotoOutput?.capturePhoto(with: photoSettings, delegate: self)

}

func photoOutput(_ output: AVCapturePhotoOutput,

didFinishProcessingPhoto photo: AVCapturePhoto,

error: Error?) {

guard error == nil else {

fatalError("Failed to capture photo: \(String(describing: error))")

}

guard let imageData = photo.fileDataRepresentation() else {

fatalError("Failed to convert pixel buffer")

}

guard let image = UIImage(data: imageData) else {

fatalError("Failed to convert image data to UIImage")

}

print(image.size)

}

}

Inside capturePhoto, we configure some settings for taking the picture, and

then set our AVCapturePhotoCaptureDelegate self as the delegate for calling

the AVCapturePhotoOutput class’ capturePhoto method. The effect of this is

that the photoOutput method we define right below will be called when a

picture is taken. After some error handling and tedious boilerplate, we end up

with a UIImage of whatever we captured at the time the user tapped the screen.

For now, we’ll just print the size to give us some sense of success. The

ultimate but most crucial step is then to replace our joyous "Tap!" message

with a call to capturePhoto in our ViewController’s handleTap method:

@objc func handleTap(sender: UITapGestureRecognizer) {

if sender.state == .ended {

capturePhoto()

}

}

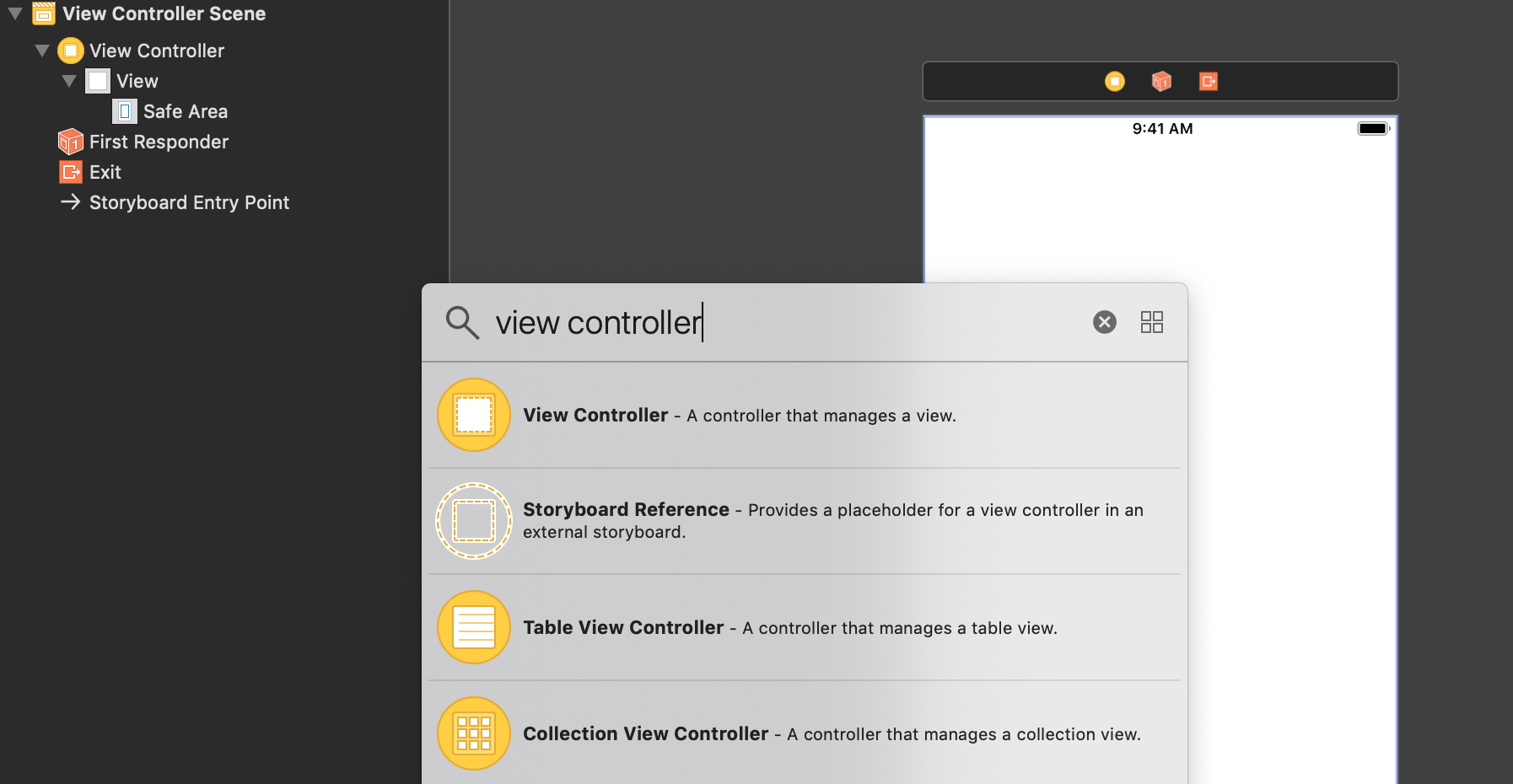

Rebuild, run, tap:

If all goes well, you should see the image dimensions in pixel units printed in the terminal.

Displaying a Captured Image

At this point, we have a way of getting a live preview of our camera as well as the ability to capture a photo. Sweet! The next step is to display this image in a new view controller. This view controller will have a button to return to the live preview as well as an activity indicator that spins while we await results from the Vision API. We will also draw the bounding box for each recognized segment of text.

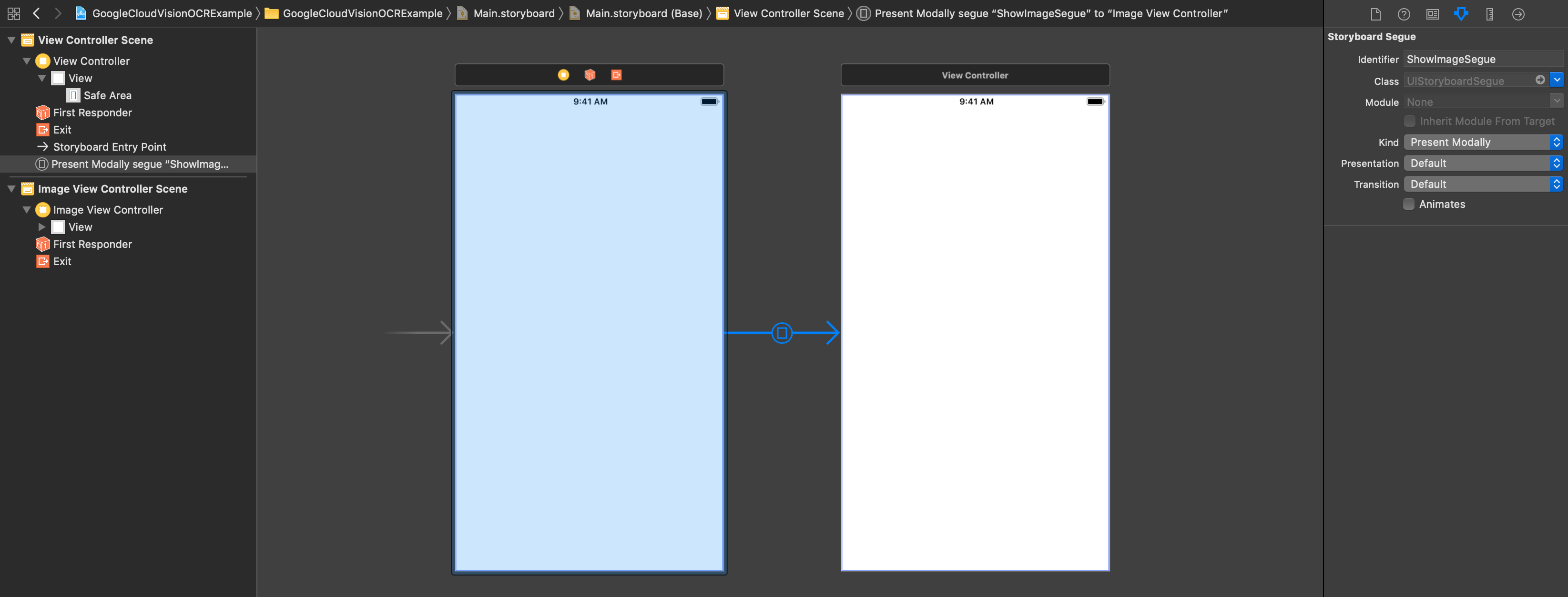

Let’s begin by creating a new view controller in the interface builder:

and connect it to our main view controller via a Present Modally segue:

I gave the segue the identifier ShowImageSegue so we can refer to it with that name in our

implementation. I also disabled the Animated checkbox since this will make the impression that the

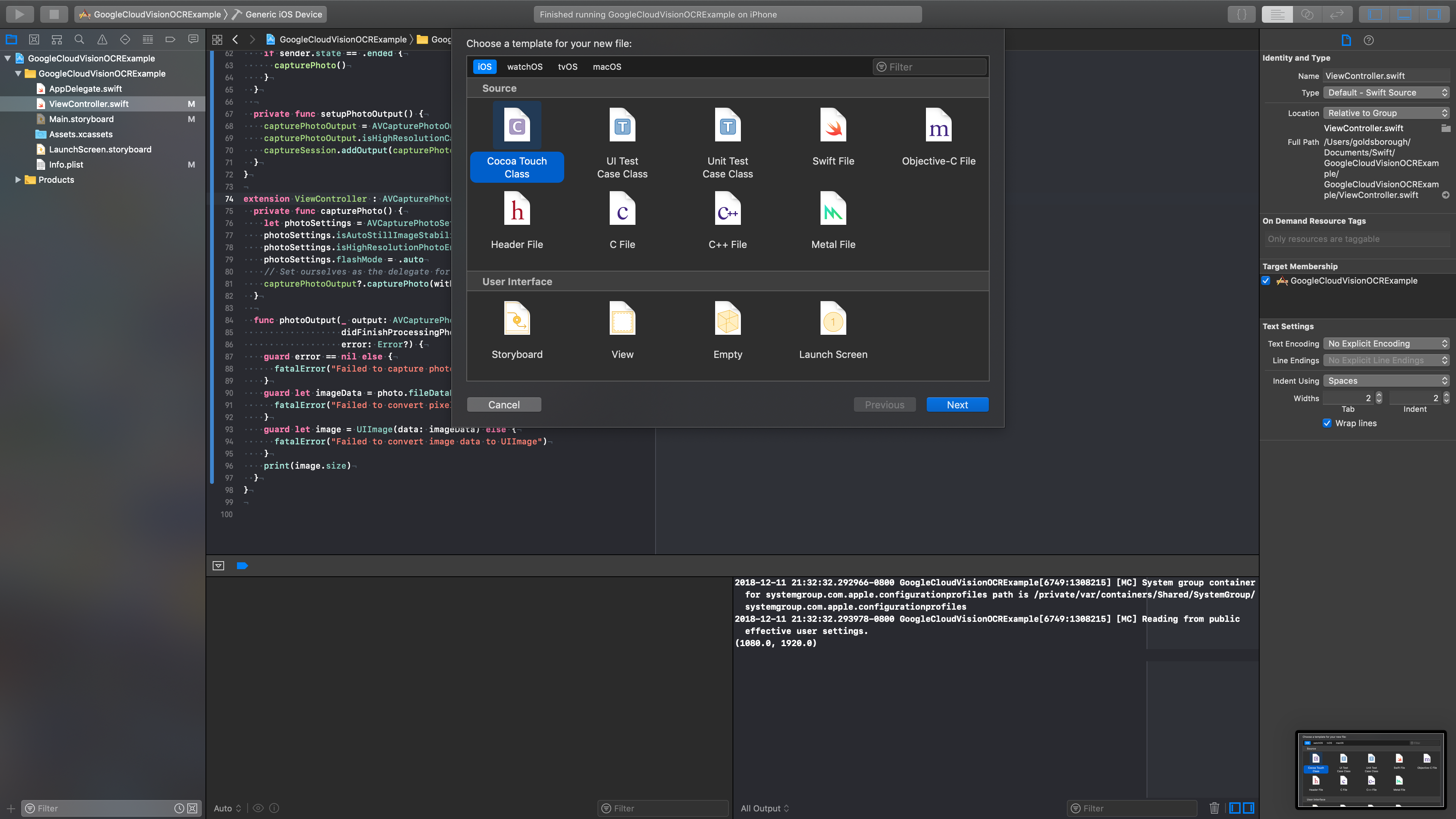

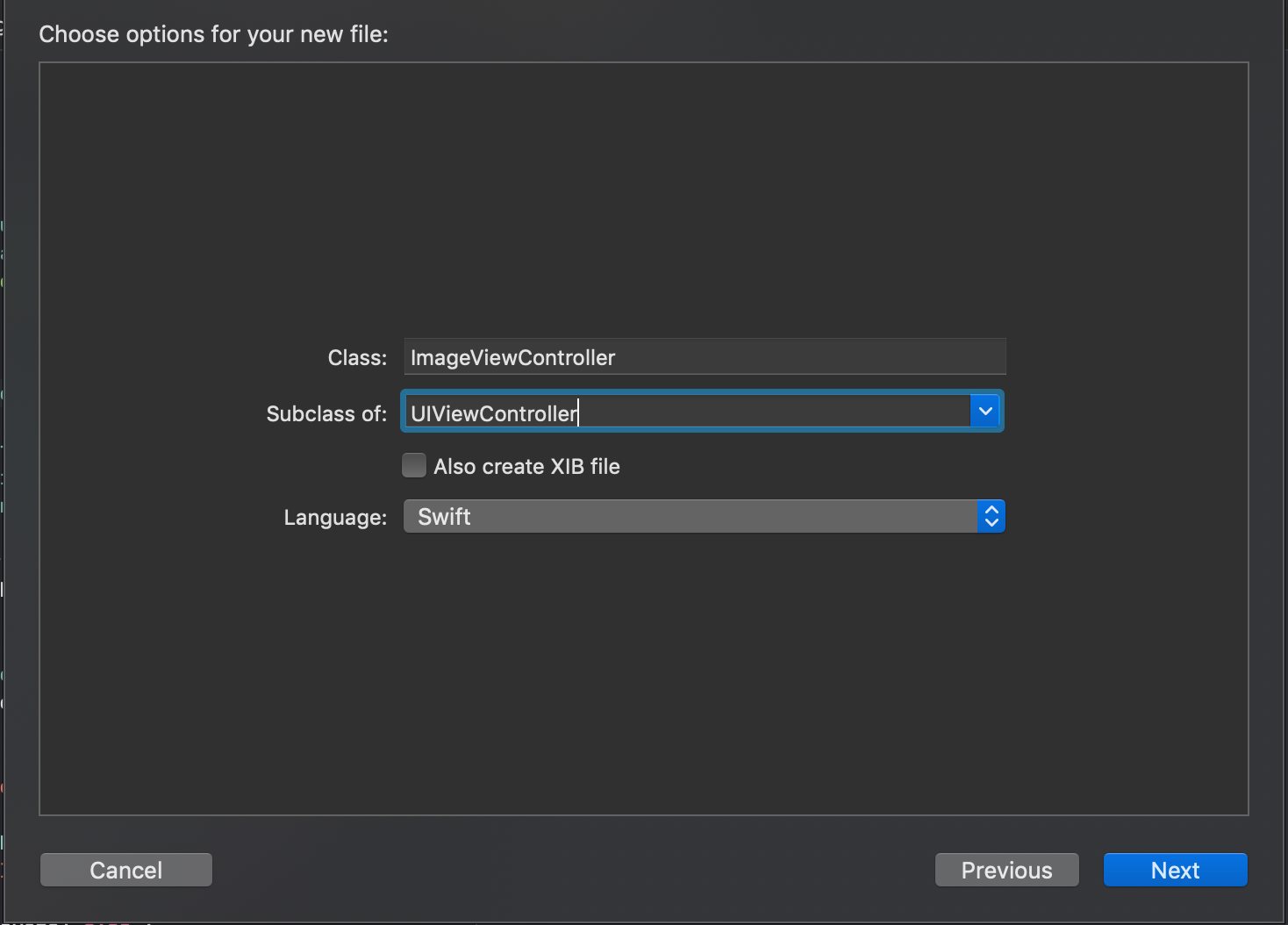

photo preview is being “frozen”, while the animation would fly the new view in from the edge of the

screen. Next, create an ImageViewController subclass of UIViewController in a new Cocoa

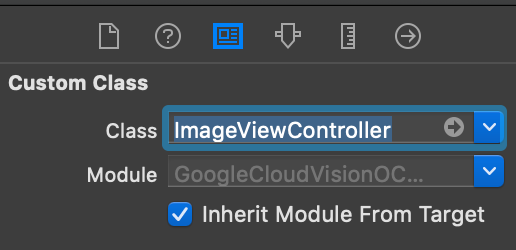

Touch file:

Also inherit the view controller from this new class in the interface builder:

Now that we have the basic visual infrastructure configured, let’s work on passing the captured

image to our new view controller, which will display the image and later on show the bounding boxes

too. For this, we’ll add a readyImage property to our main ViewController (the one we’ve been writing so far):

class ViewController: UIViewController {

var captureSession: AVCaptureSession!

var capturePhotoOutput: AVCapturePhotoOutput!

var tapRecognizer: UITapGestureRecognizer!

var readyImage: UIImage! // NEW

Next, let’s remove the print(image.size) line in photoOutput in favor of

some more useful code that performs a segue to the ImageViewController:

func photoOutput(_ output: AVCapturePhotoOutput,

didFinishProcessingPhoto photo: AVCapturePhoto,

error: Error?) {

guard error == nil else {

fatalError("Failed to capture photo: \(String(describing: error))")

}

guard let imageData = photo.fileDataRepresentation() else {

fatalError("Failed to convert pixel buffer")

}

guard let image = UIImage(data: imageData) else {

fatalError("Failed to convert image data to UIImage")

}

// NEW

readyImage = image

performSegue(withIdentifier: "ShowImageSegue", sender: self)

}

Notice that we pass "ShowImageSegue" as the identifier of the segue, as we

configured this in the InterfaceBuilder earlier. Once we initiate the segue, iOS

allows us to prepare for the transition to the new view controller in the aptly

named prepare() method. Inside, our task is to lay the groundwork for upcoming

view controller’s time to shine. For us this means passing it the image we just

captured. Unfortunately, there is to my knowledge no cleaner way to do this than

assigning to some field of the target controller:

override func prepare(for segue: UIStoryboardSegue, sender: Any?) {

super.prepare(for: segue, sender: sender)

if let imageViewController = segue.destination as? ImageViewController {

imageViewController.image = readyImage

}

}

At the moment, this code will not yet quite compile. The reason is that while we did create the

ImageViewController class, it’s still missing the image field we want to assign to here. Let’s

move on to implementing the ImageViewController and give it this field and further logic.

Implementing the ImageViewController

The minimal implementation of the ImageViewController is actually very succinct:

import UIKit

class ImageViewController: UIViewController {

var image: UIImage!

override func viewDidLoad() {

super.viewDidLoad()

let imageView = UIImageView(frame: view.frame)

imageView.image = image

view.addSubview(imageView)

}

}

We create a UIImageView to hold the image, assign it the image that was set by

the main ViewController before the segue, and add the UIImageView as a

subview of the view controller’s view. With this, you can now reload the app

and if you tap on the screen, the screen should “freeze” and display the

captured image.

Adding a Close Button

Next, let’s add a button in the top left corner that allows closing the view and returning to our live preview so that we can take a new picture:

override func viewDidLoad() {

super.viewDidLoad()

let imageView = UIImageView(frame: view.frame)

imageView.image = image

view.addSubview(imageView)

setupCloseButton() // NEW

}

private func setupCloseButton() {

let closeButton = UIButton()

view.addSubview(closeButton)

// Stylistic features.

closeButton.setTitle("✕", for: .normal)

closeButton.setTitleColor(UIColor.white, for: .normal)

closeButton.titleLabel?.font = UIFont.systemFont(ofSize: 32)

// Add a target function when the button is tapped.

closeButton.addTarget(self, action: #selector(closeAction), for: .touchDown)

// Constrain the button to be positioned in the top left corner (with some offset).

closeButton.translatesAutoresizingMaskIntoConstraints = false

closeButton.leadingAnchor.constraint(equalTo: view.leadingAnchor, constant: 20).isActive = true

closeButton.topAnchor.constraint(equalTo: view.topAnchor, constant: 20).isActive = true

}

@objc private func closeAction() {

dismiss(animated: false, completion: nil)

}

In the setupCloseButton() method, we create a new UIButton, change its style

and appearance, then add a target function which will be called when the button

is tapped, and finally constrain the button to be located in the top left corner

of the base view. Note that the button text here is the

unicode multiplication symbol,

which a suprising number of apps out in the wild actually use for their close

buttons. Inside closeAction(), we simply call dismiss() to hide the current

view controller and bring back the main one. After re-running and tapping the

screen, the ImageViewController with the captured image should (structurally)

look like this, with the close button in the top left corner:

Tapping the close button should take you back to the original live preview screen, so that you can take a new picture, close it again, take another picture and close that one too! All day and night! Fun!

Adding an Activity Indicator

Before we get to the exciting part of fetching bounding boxes and displaying

them, let’s add one more nicety to our UI: an activity indicator that is visible

while our API request and its corresponding response are floating through the

internet. We’ll hide it as soon as we are ready to display bounding boxes. Add

the following changes to the ImageViewController:

class ImageViewController: UIViewController {

var image: UIImage!

var activityIndicator: UIActivityIndicatorView! // NEW

override func viewDidLoad() {

super.viewDidLoad()

let imageView = UIImageView(frame: view.frame)

imageView.image = image

view.addSubview(imageView)

setupCloseButton()

setupActivityIndicator() // NEW

}

private func setupActivityIndicator() {

activityIndicator = UIActivityIndicatorView(style: .whiteLarge)

view.addSubview(activityIndicator)

activityIndicator.translatesAutoresizingMaskIntoConstraints = false

activityIndicator.centerXAnchor.constraint(equalTo: view.centerXAnchor).isActive = true

activityIndicator.centerYAnchor.constraint(equalTo: view.centerYAnchor).isActive = true

activityIndicator.startAnimating()

}

We add a property for the activityIndicator – of type UIActivityIndicatorView – on our

ImageViewController because we’ll need to access it to stop its animation once the response

arrives. Beyond that, setupActivityIndicator() simply instantiates the indicator, centers it

within the base view and starts its animation (a spinning wheel). The live ImageViewController

should now look like this:

Making Requests to the Google Cloud Vision API from Swift

We now, finally, come to the part of our journey where we will make API calls to

the Google Cloud Vision API to perform OCR and detect text bounding boxes in the

image the user captured. To make the API call in a more convenient fashion than

is possible with Swift and iOS’ native HTTP request library, we will use Alamofire.

Alamofire makes writing HTTP requests short and concise. It is similar in spirit

to the popular requests package in

Python. I like to use CocoaPods for dependency

management. An alternative dependency management toolchain for iOS is Carthage,

which you are free to use of course. If you go with CocoaPods, start by running

pod init in your project folder. Your Podfile should then look like this:

platform :ios, '10.0'

target 'GoogleCloudVisionOCRExample' do

use_frameworks!

pod 'Alamofire', '~> 4.7'

end

You have to close the XCode project you have open and then run pod install

from the command line:

$ pod install

Analyzing dependencies

Downloading dependencies

Using Alamofire (4.7.3)

Generating Pods project

Integrating client project

Sending stats

Pod installation complete! There is 1 dependency from the Podfile and 1 total pod installed.

Finally, re-open the GoogleCloudVisionOCRExample.xcworkspace CocoaPods

generated for us. We’re now all set to use Alamofire in our project to make

API calls to Google Cloud. For the actual request and response handling, let’s

create two new files in our project: GoogleCloudOCR.swift for the request

logic and GoogleCloudOCRModel.swift to define a set of structs into which

we’ll decode the JSON response from the API (i.e. the object relational mapping,

or ORM). Let’s begin by implementing a first version of the request logic in

GoogleCloudOCR.swift:

import Foundation

import Alamofire

class GoogleCloudOCR {

private let apiKey = "<YOUR API KEY>"

private var apiURL: URL {

return URL(string: "https://vision.googleapis.com/v1/images:annotate?key=\(apiKey)")!

}

func detect(from image: UIImage, completion: @escaping (OCRResult?) -> Void) {

guard let base64Image = base64EncodeImage(image) else {

print("Error while base64 encoding image")

completion(nil)

return

}

callGoogleVisionAPI(with: base64Image, completion: completion)

}

private func callGoogleVisionAPI(

with base64EncodedImage: String,

completion: @escaping (OCRResult?) -> Void) {

let parameters: Parameters = [

"requests": [

[

"image": [

"content": base64EncodedImage

],

"features": [

[

"type": "TEXT_DETECTION"

]

]

]

]

]

let headers: HTTPHeaders = [

"X-Ios-Bundle-Identifier": Bundle.main.bundleIdentifier ?? "",

]

Alamofire.request(

apiURL,

method: .post,

parameters: parameters,

encoding: JSONEncoding.default,

headers: headers)

.responseJSON { response in

if response.result.isFailure {

completion(nil)

return

}

print(response.result.debugDescription)

}

}

private func base64EncodeImage(_ image: UIImage) -> String? {

return image.pngData()?.base64EncodedString(options: .endLineWithCarriageReturn)

}

}

This GoogleCloudOCR class exposes only a single method, detect(), which takes an image and a

completion handler which is called once we get a successful response for our API call. This

detect() method then does two things: first, it base64 encodes the image so we can send it over

the wire as a character string; second, it makes the request to Google Cloud in

callGoogleVisionAPI. The parameters dictionary in callGoogleVisionAPI describes the API

request in the same way as we did from the command line at the start of this article. The

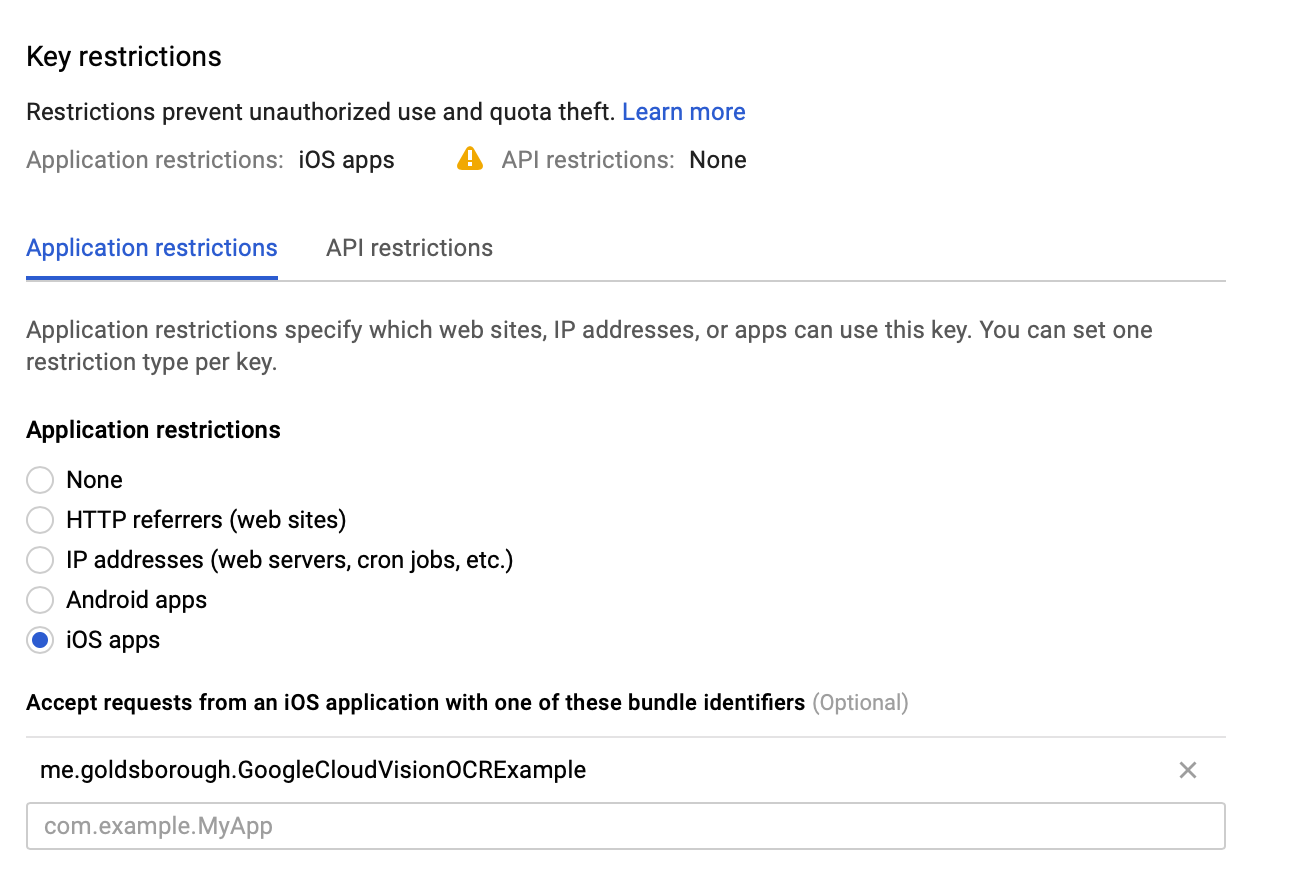

X-Ios-Bundle-Identifier header is a security measure that identifies the request source as our

application. This is not required, but certainly a very sound thing to do. To enable this access

restriction, go to your Google Cloud console and then to the Credentials section under APIs &

Services. It’ll look something like this, with

me.goldsborough.GoogleCloudVisionOCRExample replaced with your app’s bundle identifier:

We then use Alamofire.request to make the actual API call. In the completion handler, we do some

rudimentary error handling and then print the result. The latter is simply to arrive at a temporary

checkpoint before we look into actually processing the response in the next few paragraphs. Also,

before we continue, be sure to replace the <YOUR API KEY> string in the code with your actual API

key from Google Cloud. Let’s continue by wiring up this GoogleCloudOCR class we built with our

ImageViewController. Update the ImageViewController as follows:

override func viewDidLoad() {

super.viewDidLoad()

let imageView = UIImageView(frame: view.frame)

imageView.image = image

view.addSubview(imageView)

setupCloseButton()

setupActivityIndicator()

detectBoundingBoxes(for: image) // NEW

}

private func detectBoundingBoxes(for image: UIImage) {

GoogleCloudOCR().detect(from: image) { ocrResult in

self.activityIndicator.stopAnimating()

guard let ocrResult = ocrResult else {

fatalError("Did not recognize any text in this image")

}

print(ocrResult)

}

}

Inside detectBoundingBoxes(), we call the detect() method on a fresh

GoogleCloudOCR instance and give it a completion handler which, for the

moment, will simply print whatever result we funnel into it (we’ll tie together

all these loose ends soon, I promise). Later on, this is where we’ll hand the

ocrResult off to the routine that manages displaying the bounding boxes.

There is one last step required before we can succesfully run this application. If you run it as is, take a picture of something and wait for a response, it will not only be very slow, but also complete with an unsuccessful response:

SUCCESS: {

error = {

code = 400;

message = "Request payload size exceeds the limit: 10485760 bytes.";

status = "INVALID_ARGUMENT";

};

}

As you can see, the response succesfully error’d … or erroneously succeeded?

Besides making a slightly schizophrenic impression, this response is telling us

that the image payload we sent it was larger than the maximum allowed size of

1MB. An easy way to resolve this, which will incidentally make displaying the

bounding boxes later on much easier too, is to resize the image to the size of

the screen. That will definitely make the image small enough (on current phones)

and also make the image fit the screen exactly. For this, let’s update the

ImageViewController a little bit:

override func viewDidLoad() {

super.viewDidLoad()

// NEW: Resize the image to the screen size

guard let resizedImage = resize(image: image, to: view.frame.size) else {

fatalError("Error resizing image")

}

let imageView = UIImageView(frame: view.frame)

imageView.image = resizedImage // Use the resized image here

view.addSubview(imageView)

setupCloseButton()

setupActivityIndicator()

detectBoundingBoxes(for: resizedImage) // And use the resized image here

}

private func resize(image: UIImage, to targetSize: CGSize) -> UIImage? {

let size = image.size

let widthRatio = targetSize.width / size.width

let heightRatio = targetSize.height / size.height

// Figure out what our orientation is, and use that to form the rectangle.

var newSize: CGSize

if(widthRatio > heightRatio) {

newSize = CGSize(width: size.width * heightRatio, height: size.height * heightRatio)

} else {

newSize = CGSize(width: size.width * widthRatio, height: size.height * widthRatio)

}

let rect = CGRect(x: 0, y: 0, width: newSize.width, height: newSize.height + 1)

UIGraphicsBeginImageContextWithOptions(newSize, false, 1.0)

image.draw(in: rect)

let newImage = UIGraphicsGetImageFromCurrentImageContext()

UIGraphicsEndImageContext()

return newImage

}

Re-running the application now should make the request succeed with a legitimately succesful response. Pointing the camera at something with text and snapping a picture should give a response that looks something like the following (with different numbers):

SUCCESS: {

responses = (

{

fullTextAnnotation = {

pages = (

{

blocks = (

{

blockType = TEXT;

boundingBox = {

vertices = (

{

x = 119;

y = 223;

},

{

x = 268;

y = 223;

},

{

x = 268;

y = 317;

},

This is a pretty exciting step. We now have the raw data we want to display in our application – the model. The only thing left to do now is post-process and visualize this data. The first thing we want to do is transform the raw JSON response into a structured representation of Swift objects that we can manipulate better in code. Swift actually comes with a very powerful deserialization API that we can make use of here. We simply need to define a set of nesting Swift structs, implement a single decoding method per struct that tells Swift’s decoder how to convert a particular field in the response data to the corresponding field in the struct, and then finally pipe Google Cloud’s response through this tree of deserialization routines to decode it into a Swift object. While this is quite neat to work with, it’s also not the most exciting code you’ll ever write, so I’ll just paste it here in one go:

import Foundation

import UIKit

struct Vertex: Codable {

let x: Int?

let y: Int?

enum CodingKeys: String, CodingKey {

case x = "x", y = "y"

}

init(from decoder: Decoder) throws {

let container = try decoder.container(keyedBy: CodingKeys.self)

x = try container.decodeIfPresent(Int.self, forKey: .x)

y = try container.decodeIfPresent(Int.self, forKey: .y)

}

func toCGPoint() -> CGPoint {

return CGPoint(x: x ?? 0, y: y ?? 0)

}

}

struct BoundingBox: Codable {

let vertices: [Vertex]

enum CodingKeys: String, CodingKey {

case vertices = "vertices"

}

init(from decoder: Decoder) throws {

let container = try decoder.container(keyedBy: CodingKeys.self)

vertices = try container.decode([Vertex].self, forKey: .vertices)

}

}

struct Annotation: Codable {

let text: String

let boundingBox: BoundingBox

enum CodingKeys: String, CodingKey {

case text = "description"

case boundingBox = "boundingPoly"

}

init(from decoder: Decoder) throws {

let container = try decoder.container(keyedBy: CodingKeys.self)

text = try container.decode(String.self, forKey: .text)

boundingBox = try container.decode(BoundingBox.self, forKey: .boundingBox)

}

}

struct OCRResult: Codable {

let annotations: [Annotation]

enum CodingKeys: String, CodingKey {

case annotations = "textAnnotations"

}

init(from decoder: Decoder) throws {

let container = try decoder.container(keyedBy: CodingKeys.self)

annotations = try container.decode([Annotation].self, forKey: .annotations)

}

}

struct GoogleCloudOCRResponse: Codable {

let responses: [OCRResult]

enum CodingKeys: String, CodingKey {

case responses = "responses"

}

init(from decoder: Decoder) throws {

let container = try decoder.container(keyedBy: CodingKeys.self)

responses = try container.decode([OCRResult].self, forKey: .responses)

}

}

This code should go into a new Swift file called GoogleCloudOCRModel.swift.

Let’s now use this structured representation. In GoogleCloudOCR.swift, we

previously called responseJSON() on the Alamofire request object to get the

response in JSON format. Instead, we’ll now want to access the raw data coming

off the wire via responseData() and decode it into a GoogleCloudOCRResponse

object. Update the Alamofire request in the callGoogleVisionAPI() method to

look like this:

Alamofire.request(

apiURL,

method: .post,

parameters: parameters,

encoding: JSONEncoding.default,

headers: headers)

.responseData { response in // .responseData instead of .responseJSON

if response.result.isFailure {

completion(nil)

return

}

guard let data = response.result.value else {

completion(nil)

return

}

// Decode the JSON data into a `GoogleCloudOCRResponse` object.

let ocrResponse = try? JSONDecoder().decode(GoogleCloudOCRResponse.self, from: data)

completion(ocrResponse?.responses[0])

}

Notice that we call the completion handler with ocrResponse?.responses[0]. This is because we

expect the outermost responses array to only contain a single element in our case, since we only

make a single request per captured image. We can now easily print the number of annotations for our

image, back in ImageViewController.swift:

private func detectBoundingBoxes(for image: UIImage) {

GoogleCloudOCR().detect(from: image) { ocrResult in

self.activityIndicator.stopAnimating()

guard let ocrResult = ocrResult else {

fatalError("Did not recognize any text in this image")

}

print("Found \(ocrResult.annotations.count) bounding box annotations in the image!")

}

}

Re-running the application and snapping a picture with text in it should now hopefully print something like:

Found 38 bounding box annotations in the image!

We’re now all set for the final challenge on our journey: displaying the bounding boxes in the image. Onwards!

Displaying Bounding Boxes on the Captured Image

We can split the final step of displaying the bounding boxes into two separate tasks. First, let’s figure out how to simply draw the bounding box on the screen, without any interactivity. Then, because displaying the bounding box alone is not really that useful from a user interface perspective, we’ll make each bounding box into a button that the user can tap. This will allow our application to perform some action based on the text inside the bounding box that was tapped.

Let’s start with the first (easier) task of just displaying the bounding box.

Begin with the following updates to ImageViewController.swift:

private func detectBoundingBoxes(for image: UIImage) {

GoogleCloudOCR().detect(from: image) { ocrResult in

self.activityIndicator.stopAnimating()

guard let ocrResult = ocrResult else {

fatalError("Did not recognize any text in this image")

}

self.displayBoundingBoxes(for: ocrResult) // NEW

}

}

private func displayBoundingBoxes(for ocrResult: OCRResult) {

for annotation in ocrResult.annotations[1...] {

let path = createBoundingBoxPath(along: annotation.boundingBox.vertices)

let shape = shapeForBoundingBox(path: path)

view.layer.addSublayer(shape)

}

}

In the above code, we replaced the print() statement with a call to

displayBoundingBoxes(). In the implementation of that method we iterate

through every annotation (bounding box) and do two things: first, create a

UIBezierPath that goes through the vertices by which that particular

annotation is defined and second, make that path the border of a CAShape which

we can further style to our liking. This CAShape is then added on top of the

main view. The two outstanding methods look like this:

private func createBoundingBoxPath(along vertices: [Vertex]) -> UIBezierPath {

let path = UIBezierPath()

path.move(to: vertices[0].toCGPoint())

for vertex in vertices[1...] {

path.addLine(to: vertex.toCGPoint())

}

path.close()

return path

}

private func shapeForBoundingBox(path: UIBezierPath) -> CAShapeLayer {

let shape = CAShapeLayer()

shape.lineWidth = 1.5

shape.strokeColor = UIColor.blue.cgColor

shape.fillColor = UIColor.blue.withAlphaComponent(0.1).cgColor

shape.path = path.cgPath

return shape

}

You can change the line width, color and other visual properties inside

shapeForBoundingBox if you like. With the above code, however, we can already

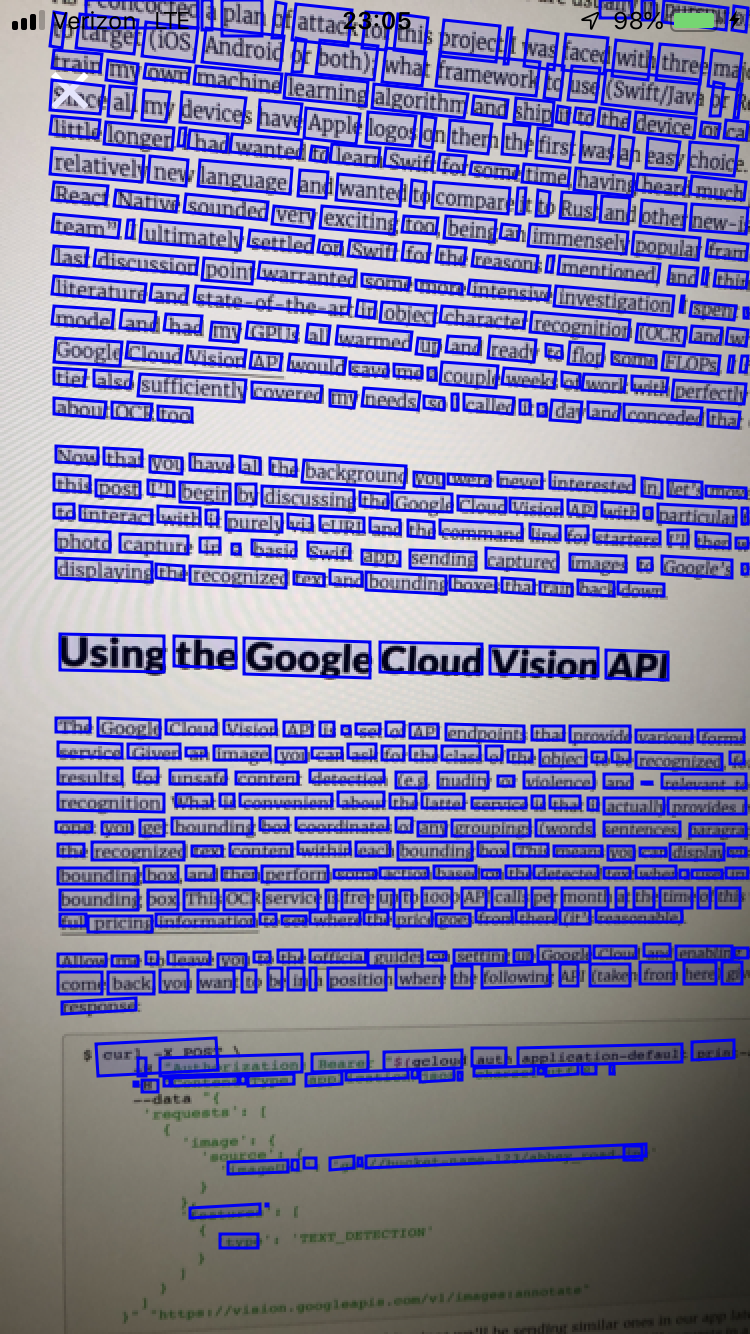

display exciting results like the following:

As you can see, the Vision API detected the bottom text and the word “gum”, but not the word “Orbit – that one is probably too stylized. Pretty cool! But does it scale? Let’s try more text:

Looks like it does!

Making the Bounding Boxes Interactive

Let’s now make these bounding boxes more interactive. What we want is a subclass

of UIButton that we can give the shape and look of a bounding box. This is

actually a little difficult because a UIButton can only have a rectangular

frame. This means we’ll have to manually detect when the user really touched

down inside the bounding box shape and not the surrounding rectangle the

UIButton actually lives in. Other than that, the implementation of this

BoundingBoxButton is fairly straightforward:

import UIKit

class BoundingBoxButton: UIButton {

let text: String

let path: UIBezierPath

required init(path: UIBezierPath, text: String) {

self.text = text

self.path = path

super.init(frame: path.bounds)

path.apply(originTranslation(of: path, to: path.bounds.origin))

addTarget(self, action: #selector(touchDown), for: .touchDown)

}

required init?(coder aDecoder: NSCoder) {

fatalError("init(coder:) has not been implemented")

}

override func draw(_ rect: CGRect) {

let shape = CAShapeLayer()

shape.lineWidth = 1.5

shape.strokeColor = UIColor.blue.cgColor

shape.fillColor = UIColor.blue.withAlphaComponent(0.1).cgColor

shape.path = self.path.cgPath

layer.addSublayer(shape)

}

@objc func touchDown(button: BoundingBoxButton, event: UIEvent) {

if let touch = event.touches(for: button)?.first {

let location = touch.location(in: button)

if self.path.contains(location) == false {

button.cancelTracking(with: nil)

}

}

}

private func originTranslation(of: UIBezierPath, to: CGPoint) -> CGAffineTransform {

return CGAffineTransform(a: 1, b: 0, c: 0, d: 1, tx: 0, ty: 0)

.translatedBy(x: -frame.origin.x,

y: -frame.origin.y)

}

}

Let’s discuss this code, which should go into a new file called

BoundingBoxButton.swift. We give our BoundingBoxButton a custom constructor,

which takes the path of the annotation and the text it represents. Both of these

pieces of information come from the backing model in our

GoogleCloudOCRResponse object. The custom constructor calls the

init(frame: CGRect) constructor which the UIButton has by default, in order

to create the surrounding frame in which the button will live. As I mentioned,

UIButtons – in fact UIViews in general – can only have rectangular frames.

Therefore, we need to supply such a rectangular frame, which we get very

conveniently via path.bounds, which spans a rectangle the UIBezierPath, no

matter how windy and complex, will fit into. We then apply a CGAffineTransform

to the path. This is because we created the path relative to the original image

frame, but now want to place it within the frame of the button, which may have a

different origin.

We also add a target function for the .touchDown event. The connected

function, here also called touchDown, takes care of determining when the user

actually clicked inside the bounding box’s path, as opposed to the surrounding

space of the button’s frame. In the latter case, we cancelTracking.

Lastly, draw() is exactly the code we had in shapeForBoundingBox earlier,

just that we directly add this shape to the BoundingBoxButton.

And that’s it for the implementation of the BoundingBoxButton. Next, let’s

create one such buttton for every annotation inside of our

displayBoundingBoxes() method in ImageViewController.swift. It should be

updated to look like this:

private func displayBoundingBoxes(for ocrResult: OCRResult) {

for annotation in ocrResult.annotations[1...] {

let path = createBoundingBoxPath(along: annotation.boundingBox.vertices)

// Create a BoundingBoxButton for this path and the text inside the bounding box.

let button = BoundingBoxButton(path: path, text: annotation.text)

button.addTarget(self, action: #selector(boundingBoxTapped), for: .touchUpInside)

self.view.addSubview(button)

}

}

@objc private func boundingBoxTapped(sender: BoundingBoxButton) {

let alert = UIAlertController(title: sender.text, message: "", preferredStyle: .alert)

alert.addAction(UIAlertAction(

title: NSLocalizedString("Yey", comment: "Default action"),

style: .default,

handler: nil))

self.present(alert, animated: true, completion: nil)

}

This will add one BoundingBoxButton per annotation to the screen. When tapped,

we should see the contained text in a message box. Let’s try it out! First we

take a snap:

Then tap the bounding box containing the word “fresh” …

Yey! That worked, and also concludes the implementation of our innovative, breathtaking, ready-to-be-award-winning app.

Outro

In the beginning of this post we set out to use the Google Cloud Vision API – which provides access to world class machine learning algorithms – and build a tiny sample application with it. We first looked at talking to this API purely from the command line and then in the context of a more beefy iOS application written in Swift. I hope you learned a thing or two! More importantly, however, I hope this sample application gives you food for thought on many real world problems you can solve using this or other APIs, or maybe even by training your own machine learning models (with PyTorch, of course).

Personally, I found it exciting how quickly I could go from an idea that required the use of machine learning to having a minimal prototype up and running and working sufficiently well to prove or disprove the idea’s feasibility. The tools to solve the world’s hard problems, if they’re solvable with AI, are certainly there. Time to make use of them.

P.S.: The full code for the Swift app we built here can be found in this repository.