I’m currently in the very fortunate position of taking an entire year off from university to do internships at Google, Bloomberg, Facebook and an AI startup. I feel like in the past few months, I’ve already learnt an incredibly intensive amount about an incredibly extensive spectrum of topics, ranging from core technical skills to the art of human interaction. However, besides learning hard skills and soft concepts, I’ve also learnt a great deal about how to learn more effectively. Over the past few months I’ve spent quite a number of semi-sane moments thinking about this last topic and decided to scribble down a particular mathematically inspired thought over the next few paragraphs.

Probably the most crucial insight one can make about learning is that effective learning is not a passive or reactive, but absolutely an active process. In a sense, we may sometimes take the activity of learning for granted, treating it as an automatic thing like the movement of an arm or a sneeze. At the same time, most of us do notice at one point that we can influence our own learning process, for example by making mnemonics, learning in groups or associating concepts with particular dances. Note that the latter method is sometimes frowned upon by instructors in practice, as starting to breakdance to remember how to integrate logarithms may come across as an attempt to disturb the class. In any case, if we reflect a bit further about the idea of learning how to learn, we notice that it is actually a very powerful concept, because it is inherently “recursive”, like a computer program that modifies itself to modify itself better.

Expanding on the last thought, we can try to come up with a simple mathematical model of learning and learning how to learn. Intuitively and idealistically, if we learn how to learn more effectively by a certain amount $\lambda$, this means that the next time we learn how to learn more efficiently, we’ll end up in a position where we learn $\lambda \cdot \lambda = \lambda^2$ times more effectively than at the beginning. As such, according to this simple model, if we were to entirely devote our time to learning how to learn more effectively, the quality of our learning $\mathcal{L}(t)$ as an exponential function of time $t$ would be given by

\[\mathcal{L}(t) = l_0 \cdot \lambda^t,\]where $l_0$ is some initial ability of learning we possessed at the start of the experiment. While this exponential model is fun to toy around with, on second thought, a more realistic (but obviously still idealistic) model of a person with good learning habits – let’s call this a strong learner – may really be a linear one. So let’s assume from now on that if a person were to sit down and learn how to learn more effectively, their ability to learn would increase by a fixed amount $\kappa$ each time, giving

\[\mathcal{L}(t) = \kappa \cdot t + l_0.\]So if we define a strong learner as a person who can increase his or her capacity to learn over time, it begs the question of what it means to be a weak learner. To conceptualize the idea of weak learning, imagine a robot roaming in a bounded, grid-like maze with the goal of finding the exit of the maze. The one additional characteristic of the maze is that it contains cliffs, which hurt the robot when it falls down one of them. The strategy of the robot is very simple. At every position in the maze, it randomly moves either north, west, east or south to the tile in the grid adjacent of wherever it currently stands. If a move in a particular direction is blocked by a wall, it picks another direction. If the new position is a cliff, harm is inflicted on the robot. If not, it picks a direction anew. In either case, the robot’s unique ability is that it can remember what tiles in the maze were cliffs and which weren’t. What this really means is that for each new position the robot encounters, its knowledge is increased by a fixed amount. However, what does not increase is the robot’s ability to take in knowledge faster over time, since it follows such a simple and fixed (deterministic) strategy. As such, while its knowledge is linear, its learning is constant.

What is essential to notice at this point is that mathematically, learning or

the ability to learn is really not an absolute quantity. What learning really

is, is the rate of change, i.e. the derivative, of knowledge (while

fundamentally trivial, I find this a very pleasing mapping of these “soft”

philosophical concepts to the domain of mathematics).

Learning is the derivative of knowledge.

Let $\mathcal{K}(t)$ be the function describing the total amount of knowledge possessed by a person at time $t$. Then we simply have

\[\frac{\mathrm{d}}{\mathrm{d}t}\mathcal{K}(t) = \mathcal{L}(t).\]Since the learning of a strong learner is linear, the knowledge of that person increases quadratically. More insightfully, a person that takes in the same amount of knowledge at all times posseses only a constant ability to learn.

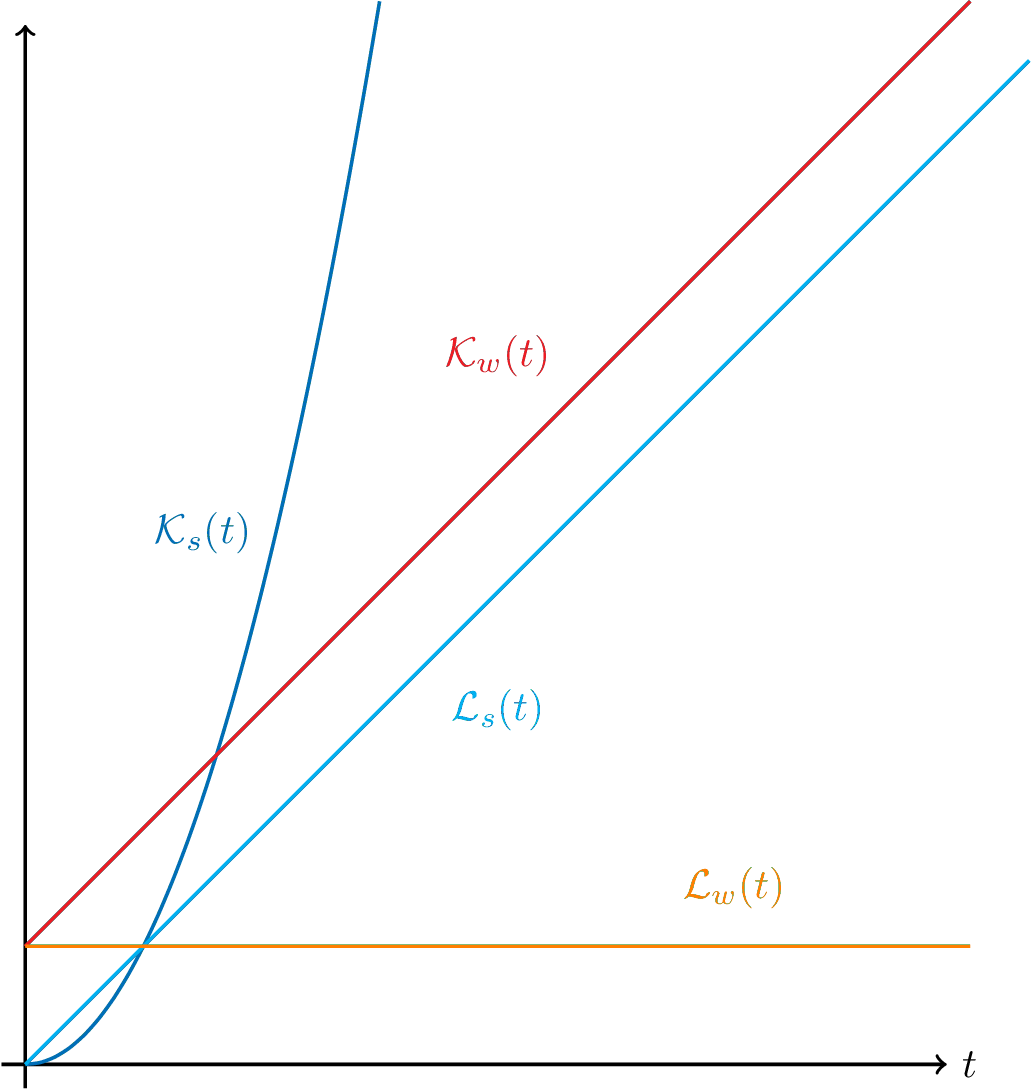

The knowledge and learning functions of a strong learner ($\mathcal{L}_s(t), \mathcal{K}_s(t)$) and weak learner ($\mathcal{K}_w(t), \mathcal{L}_w(t)$).

The knowledge and learning functions of a strong learner ($\mathcal{L}_s(t), \mathcal{K}_s(t)$) and weak learner ($\mathcal{K}_w(t), \mathcal{L}_w(t)$).

Interestingly, what we notice in both cases is that the learning function $\mathcal{L}(t)$ is always strictly positive, both for the strong and weak learner. This does make sense, since even if a lobotomized person with sub-average IQ goes out of his apartment, he will learn things simply by interacting with the environment around him. At the very least, this learning happens passively through biological processes that are outside of his control (the only learning that does not require conscious effort), such as associating surrounding sounds with his home more strongly because they’ve occurred the third morning in a row.

Of course, what this current model is not considering is the fact that humans do, also, lose knowledge over time. This is simply what we know as forgetting. While everyone forgets, especially as we get older, it would require quite extreme circumstances, like dementia, to have the rate of forgetting be higher than the influx of knowledge. Sure, if you sit in a white room for ten years staring at the same white wall throughout, the total amount of knowledge you will have lost by the end of the period will be greater than the amount of knowledge taken in. However, in the usual setting, I would say that this is not the case.

Now, we’ve established that both strong and weak learners have a positive knowledge derivative. Nevertheless, it is clear that strong learning is a more optimal property to have. How could we quantify this, or at least conceptualize it, in our current model? Looking at the figures above, we notice that the one fundamental difference between a strong learning pattern and a weak learning pattern is that the learning of a strong learner increases over time. More precisely, the slope of a strong learning curve is positive, while that of a weak learner is zero. So, really, what differentiates a strong learner from a weak one is the rate of change of learning. Since learning is itself the derivative of knowledge, it must be the second derivative of knowledge, i.e. the concavity, that sets good learning habits apart from bad ones.

I find the last discovery to be particularly interesting, especially if we move away from the mathematical model and relate these findings back to reality. What the last paragraph implies is that, to move ourselves forward in our careers, be they personal or professional, at a steady pace, our aim should not just be to learn things, but to learn increasingly more and more effectively over time. The total amount of our knowledge will always be increasing as we grow older (and wiser). The way we can set ourselves apart from others is by ensuring that also the rate of our learning (the second derivative) increases over time. If the concavity of our knowledge is positive (up), this means that we will be able to progressively take in more and more knowledge (up to some terminal rate). In practice, I’ve found one of the best ways to achieve this goal is to ask questions and observe how my peers tackle challenges, how they keep themselves up to date about the newest advances in their field and also what methods they use to learn effectively.

This blog post was not intended to be a formal investigation of the biological or psychological underpinnings of learning. Nor was it an attempt at creating an exact mathematical model of learning. Rather, it was a thought. A thought on what it means to learn and what it means to learn how to learn, effectively. I believe very few of us actively pursue the latter and make sure the concavity of our knowledge is up. I hope these scribblings inspire you to do so.