Likes, Facebook and internet.org

Likes, Facebook and internet.org

“Hackathons are an important part of Facebook’s culture. In fact, many features that you see in the app today were invented and prototyped at Hackathons, like the timeline or videos on Facebook. For a full day, people from various teams and various backgrounds come together to create something new. We ask that they be creative and that they be bold. Actually, there was this one time at a Hackathon where some folks were really unhappy with this wall we had in the office that was separating them from part of their team. So they just took a sledgehammer and tore down the wall.”

We all laughed. A few hours earlier a dozen other interns, me and a hand-full of engineers, designers and project managers from London and Tel-Aviv had entered the orientation room where one of the instructors was currently giving a talk on Facebook’s culture and values. The walls of the room were filled with posters displaying messages like Focus on impact, Nothing at Facebook is somebody else’s problem or What would you do if you weren’t afraid? On the mixture of beach chairs, couches and old leather chairs we were now sitting on we had each found two things: a notebook and a sticker saying this is your company now. So Facebook was my company now and this was my chance to leave an impact in the three short months of my engineering internship at Facebook London this summer. Over the next few paragraphs I want to share a few thoughts and insights on my time at Facebook.

Signing Up

Before diving into the description of my days at Facebook, let me take a step back and talk a bit about how I ended up there to begin with. At this moment, Facebook as a platform and company is growing tremendously. More than two billion people actively use Facebook every month – a service that is running on millions of servers in nine data centers around the world. Then there’s Whatsapp with a billion users and Instagram a few hundred million shy of that. Running a platform that serves a quarter of the world population is, well, really, really hard and Facebook is looking for the best and brightest generalists and domain specialists to move it forward and help it scale. For interns specifically, there’s probably a few ways to get noticed by a university recruiter or talent sourcer. There’s coding competitions, university events, online applications and then there’s also the option of just waiting for a message to pop up on LinkedIn. The latter was my “path”. Around October 2016, while I was still interning at Google, I got a message from a university recruiter asking me if I was interested in applying for a summer internship at Facebook.

After a brief and very friendly phone call with a recruiter from the London office, I scheduled my first interview for a Software Engineering (SWE) internship towards the end of October. Besides SWE interns, Facebook also takes on interns in Production Engineering (more commonly known as Site Reliability Engineers (SREs) in industry) that do just as much coding but supposedly a bit more of the operations side and keeping clusters alive; Data Engineering, which is focused on managing large datasets and building pipelines used by data scientists and Facebook’s machine learning systems; Product Design and business roles outside of engineering. Note that, from what I gathered when talking to other interns later on, not everyone jumps straight to interviews. Some of the interns had to do online coding challenges first.

My first interview was with an engineer from Menlo Park over Skype. In general, Facebook SWE interns have to pass two interviews (scheduled separately). The first one is easier, the second one harder. The interview questions themselves are the usual algorithm and data-structure focused questions that are commonplace at big tech companies like Google, Microsoft et al. I can’t say if they were harder or easier than at Google, I think this depends entirely on the interviewer one gets and what their favorite interview question is. To some extent that part is luck, so the only thing I can recommend is to practice and make skills outweigh the element of chance as much as possible. Either way, I passed the first round of interviews and had the second round scheduled for around three weeks later. This is actually super far apart and made it harder to stay fully prepared, but according to my recruiter interview slots were just filling up really fast. I passed the second round in late November and had my offer a week later.

The project selection at Facebook is very different from Google. At Google, once you pass the interviews, you get thrown into a pot of candidates. Internally, engineers with projects in mind then get to pick and choose candidates that would best fit their project and can then evaluate them further in a 1:1 conversation. This process can be quick and happy, or excruciatingly long and scary because there is a chance that no one picks you, meaning that even though you passed all the interviews and made it 99% of the way, you don’t end up with an internship at all. Bad luck (I met a guy to whom that happened – it was sad). At Facebook, things are different (that is an overarching theme). Around one month before the internship, we got an online form in which we could write a paragraph about our interests, skills and what teams we would like to join. A few weeks later you then get an email telling you what team you got paired up with. The consensus of opinions from all interns I’ve spoken to is that whoever makes the project selections, they are really good at it – all interns seemed very happy about their project. The interesting thing about my team allocation was that it didn’t fit at all what I had written in that paragraph about my interests (machine learning), but did fit perfectly to my background and skills (infrastructure and distributed systems). So they had definitely done their homework and I was happy too.

Weeks 1 and 2: Welcome to Facebook

The activities in the first two weeks of my internship were centered around four or five different themes: exploring the Facebook London office; getting to meet my team in London and Menlo Park; figuring out the details of my project and overall technical ecosystem at Facebook; attending exciting intern events and lastly eating free food (ok, I admit that was a very prevalent activity throughout my internship).

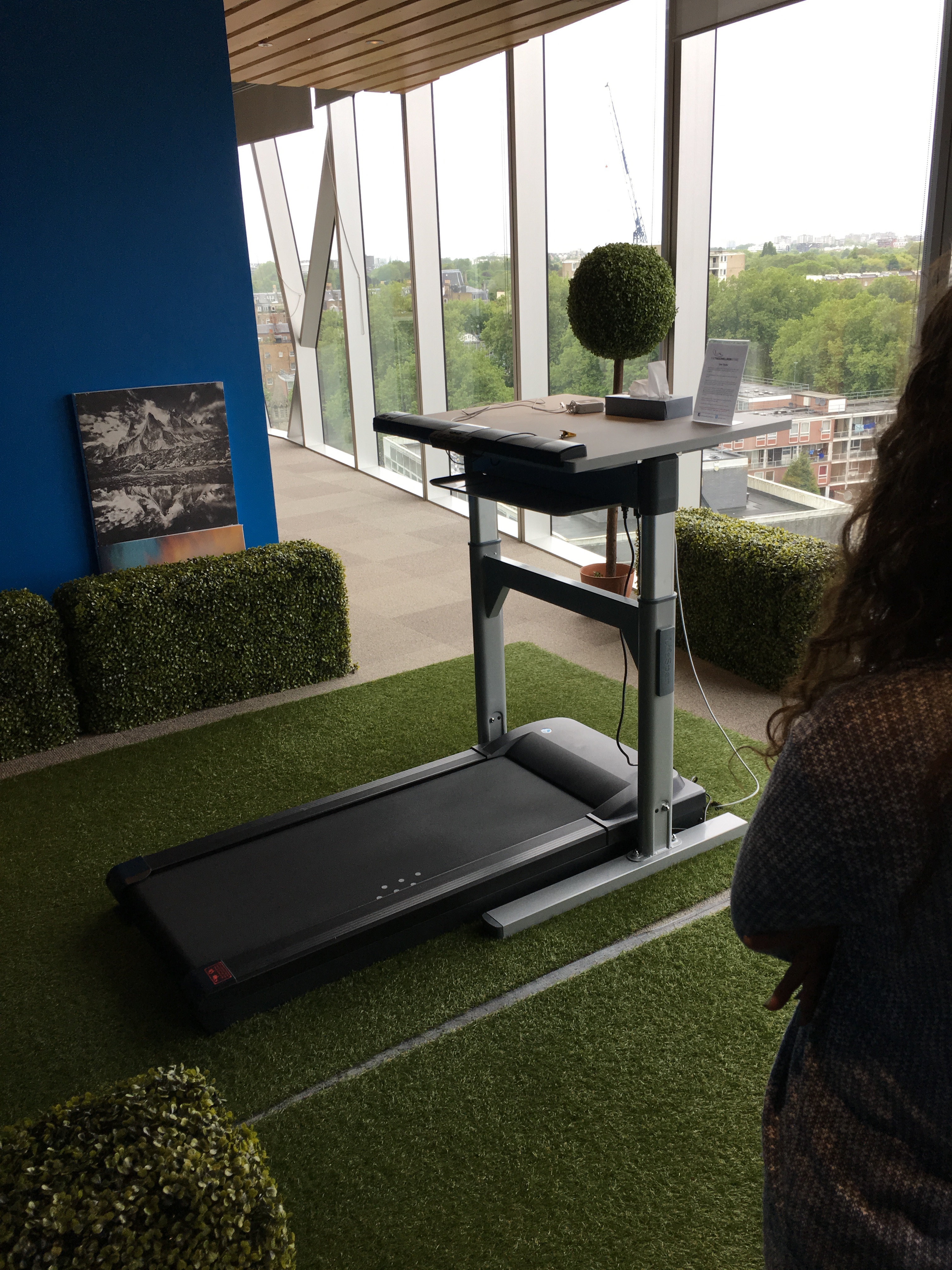

Work? Exercise? Why not both?

Work? Exercise? Why not both?

London is Facebook’s third largest engineering office after the HQ in Menlo Park, California and Seattle, Washington. Other offices include New York, Paris, Tel-Aviv and some other very small, non-engineering satellite offices in other places around the world. In London, Facebook currently has three separate offices and is about to open a new, larger one that will aggregate employees from all three into one. In my post about my Google internship, I described the Google London office as a playground inside a five star hotel. This also holds very much true for Facebook London, although the Facebook office seems much more fun, quirky and colorful. There’s a full-fledged sweet shop, an Oculus Rift station, pool, ping pong and foosball tables (the usual stuff), comfy couches and snacks and drinks floating around.

The first two weeks were also very much about getting to know my peers and larger team. In general, every intern is assigned an intern manager. For SWE interns, this is usually an engineer (who has been at Facebook for at least 6 months). The intern manager’s task is to set out a project roadmap, coach you, provide feedback on a rolling basis and ultimately also have the biggest say about your final evaluation. In my case, this relationship was really awesome. I got to sit right next to my manager, meaning I could ask lots of questions in the beginning and then slowly grow my own wings once I started having a general sense of direction. Besides my intern manager, interns are encouraged to find at least two other peers. Those should simply be two other engineers on your or another team that you work closely with and can form a substantive opinion about your work at the end of your internship. Overall, I integrated very well and quickly into my team, who were also exceptionally welcoming, and immediately got very buddy with everyone. I also got to meet with our team manager, a very senior engineering manager who lead the high level technical direction of the team, besides building, managing and growing the team and other things managers do (meetings, meetings, hiring and meetings). One fact of life for many teams in London is that they are split, the other part usually being in Menlo Park. This means I also got to know some of the engineers in Menlo Park in my first two weeks (via video conference). The fact that teams in London often have to collaborate with people in Menlo Park, with an eight hour time difference, is actually one of the more intriguing aspects of the London office, as I would learn and observe in the coming weeks.

Sweet Life

Sweet Life

One thing that you would expect to be on a list of things I did during the first two weeks of my internship is exploring London and surroundings. However, by the time of my Facebook internship I had already been in London for almost a year, so I had most boxes ticked on that front. Nevertheless, I did get to explore my new neighborhood, since Facebook provided us with free corporate housing for the entire duration of our internship.

Mah crib

Mah crib

Weeks 3-5: Digging In

After the first couple weeks I had settled in nicely into my project, my team and the office. I had become familiar enough with the quadrant spanning from my desk to the cafeteria, to the coffee machine, to the snack corner and back to my desk that I could begin diving deep into the technical and personal challenges ahead. Let me go into a bit more detail about the engineering environment at Facebook. Feel free to skip this part if you’re less fluent in speaking Nerd!

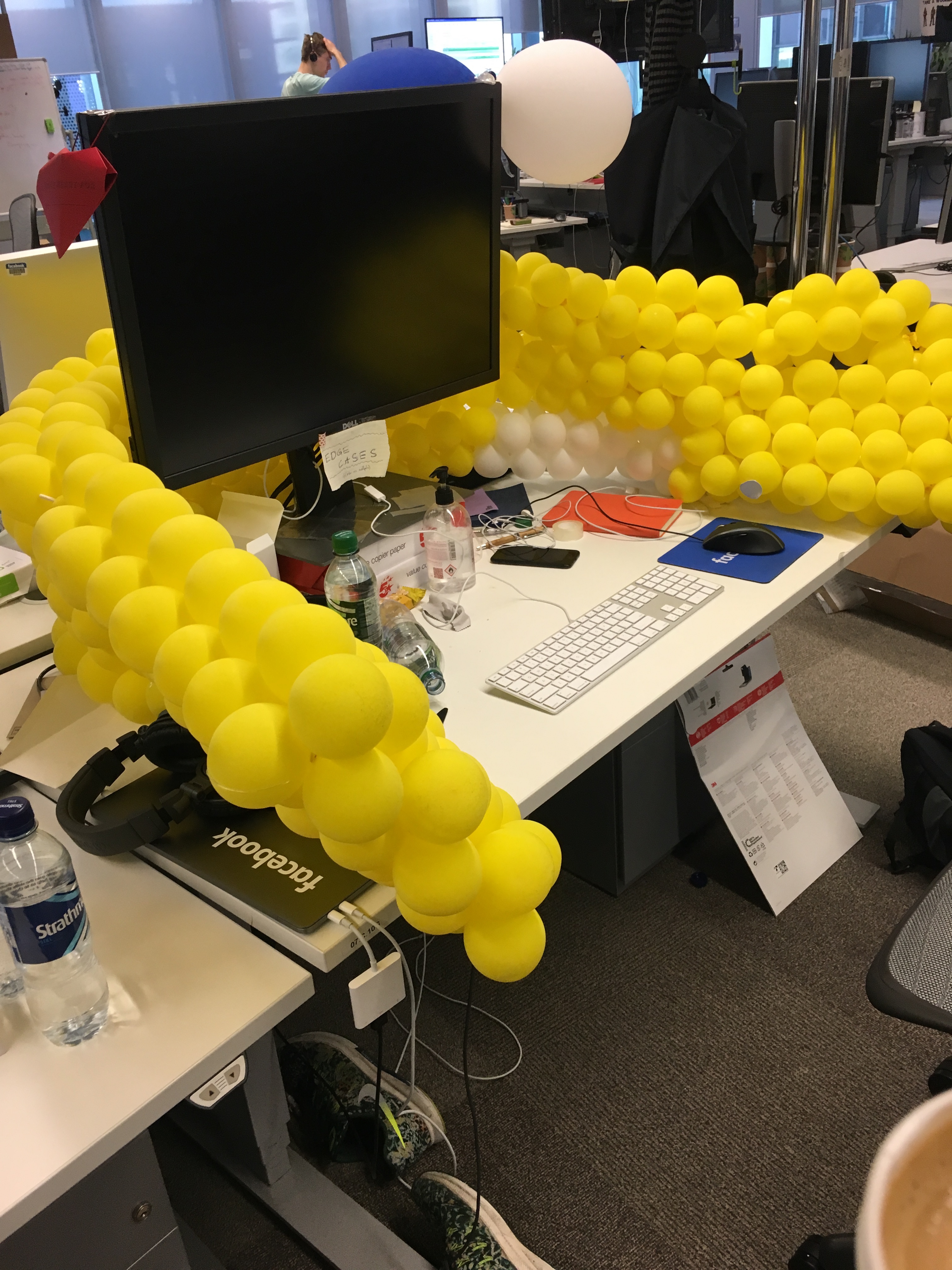

My desk and my balloon wall

My desk and my balloon wall

By week two, I had started to get a more solid grasp on the engineering infrastructure and landscape at Facebook. This, in itself, is not such an easy task. Like most big tech companies, Facebook develops very large parts of its systems and infrastructure in-house rather than relying on external software. This is not because Facebook has anything inherently against existing open source projects (almost everything Facebook develops gets open-sourced anyway), but usually because existing solutions don’t scale to 2 billion people. So if you’re a front-end developer, you’ll have to get your head around Hack, React or Flow; if you’re an AI researcher or in Applied Machine Learning (AML) it’s FBLearner, PyTorch and Caffe2; if you’re in infrastructure it’s Folly, Thrift, RocksDB, Zstd and Buck – the list goes on. Fortunately, all of these technologies are open source and used throughout the industry, so it’s not a long shot for someone starting at Facebook to be familiar with some of these tools. Either way, there is a ton of internal documentation and wikis, tons of classes and courses on the essential Facebook stack and tons of insanely smart people all around you, so getting up to scratch goes fast. Also, one of the beautiful things about Facebook is that the entire codebase is open and accessible to anyone (in a huge monorepo), so if you’re ever wondering how some internal technology works, you can just look how it’s implemented or used elsewhere.

Next to learning about cool Facebook tech, I was also more than busy and entertained with my project. The particular corner of Facebook I was working on was a highly distributed log and message distribution framework at the core of Facebook’s infrastructure. The roadmap my mentor had laid out for me generally centered around simplification and redesign of the codebase as well as increasing throughput and efficiency, with enough flexibility and space for my own ideas and contributions. Even though I was quite far away from the actual Facebook application, almost everything at Facebook depended on the stuff I was touching and improving, which was a very nice feeling. In general, one of the most exciting things about working at Facebook is that everything is 1000 times the scale you are usually used to. One million users? I raise you two billion. A few hundred servers? I raise you millions. Gigabytes of data going through your pipelines? I raise you petabytes.

To be a bit more specific, the majority of our codebase was in C++, which is the most dominant language in Facebook’s backend. There is also a lot of Python, for anything less performance critical, like Mercurial and a lot of DevOps stuff. Rust is also popping up in more and more places, for example in the realm of source control. Occasionally, you’ll also come across some D (since Alexandrescu worked at Facebook) and Go. A cool fact is that Facebook is also very open to and fond of functional languages. Infer, its static-analysis system, is written in OCaml, as is Flow, the Javascript type checker. There’s also Haxl, a Haskell library used for things like anomaly detection. Of course, Facebook is also extremely active on the frontend (although this is not as much my domain). Web stuff is usually written in PHP and Hack (running on the HHVM), which actually isn’t as bad as I thought.

By the end of week five, I had my midpoint review. Even though internships are 12 weeks long, the core evaluation period is only ten weeks, so the middle of your performance cycle is officially the end of the fifth week. The midpoint review is basically an assessment of your performance, calibrated against the progress of other interns. If you’re on track, your manager tells you that you are “trending towards an offer” (either for a returning internship next summer, or a full time position); if not, you get feedback on how to turn the ship around. Fortunately, I was trending towards an offer, which I celebrated with excessive amounts of ice cream the next day.

Weeks 6-8: Living the Facebook Life

Around week six it was finally happening: a Hackathon was coming up! Of course, Facebook can’t just have a Hackathon in the office. Needless to say, they rented the entire London Velodrome, the venue of the cycling competition at the 2012 summer olympics. This was actually my first hackathon ever (also outside of Facebook), so I was very excited.

The way it works is that anyone at Facebook can propose a project for the hackathon in advance, and anyone who wants to join a team can simply sign up. This is a really wonderful opportunity to meet new people from different teams at Facebook, be it engineers, designers, janitors or project managers – everyone hacks. Because none of the proposed projects were quite to my liking, I went ahead and proposed my own. This proved to be a very exciting experience, since a large group of full-time employees and interns joined my team and we not only got a prototype up and running by the end, I even ended up shipping it to production (it’s an internal tool, but it’s still used by a lot of people now). At this hackathon I also experienced one of the things I love most about big companies: you sometimes end up sitting next to or even working (or hacking) with people who just seem like ordinary, friendly chaps, but turn out to have invented the internet or done some other amazing thing. In my case, one of the people in my hackathon team (writing my Python server for me) was one of the top 10 ranked people on StackOverflow; which is a pretty big deal for some folks.

A wild tribe of Facepeople, hacking

A wild tribe of Facepeople, hacking

Facebook has a very rich culture outside of Hackathons too, of course. People are extremely friendly, smart and like moving fast. If I had to pick two words to describe the culture, I’d probably go with flat and open.

With flat, I mean that the hierarchy at Facebook is extremely horizontal. There’s multiple points to this. For one, with around 20,000 employees, Facebook is one of the smallest of the tech giants in terms of staff, which means that things still feel much more startup-y and flexible and management is still focused on scaling to the next billion users and not office politics, like at most other big tech corps. I also find that the open floor plan makes the hierarchy feel flatter. You get engineering directors and extremely senior engineers and managers sitting with new hires, interns and everyone else. In fact, one of the things that struck me most in my time there was seeing an engineering director helping out an intern with his code. Having folks with hundreds of reports and a million things on their mind still find the time and humility to help an intern with a simple question requires a very special kind of culture. Another minor detail that I found interesting is the publicity of seniority at Facebook. Like at Google, Facebook engineers have ranks. At Google, everyone can see everyone else’s rank (with the right Chrome extension) and this obviously leads to a significant bias during interactions. At Facebook, you can’t see other people’s rank. You judge them by their actions and behavior instead of their label. I prefer that approach.

With open, I mean that everything at Facebook seemed very transparent to me. This starts with the codebase, where everyone can access everything freely and without restrictions. Compare this with Apple, where engineers can only see the code they immediately work on. It continues with the fact that there are townhalls and Q&As with Zuck every single week, where anyone can ask a question, and often with Sheryl Sandberg, Chris Cox and other execs. There were also some Q&As specifically for interns, where I got to chat with Oculus’ VP of Product. Outside of this public accessibility, there was generally a lot of internal communication about any important changes to the company’s policy or new features and products Facebook was working on.

Next to working, working and managing my work-work balance, I of course also did a lot of fun stuff with other interns. Mostly, this was just playing/losing a casual game of pool after dinner. There were also a few cool group events throughout our internship, like going to a musical, go-karting or a graffiti workshop.

Weeks 9-12: Wrapping up

I spent the last few weeks of my internship implementing a couple more features and finishing up a couple more tasks for my project, but also focused more and more on helping with the release of our code. Since the system I was working on was such a crucial piece of infrastructure, it had a relatively slow and incremental release process, shipping to gradually more and more servers in our fleet over the period of a few weeks. This was a very interesting, although extremely stressful, switch from my usual coding duties to activities like monitoring the health of our system as it was rolling out, hotfixing bugs as they popped up (and sometimes rolling back) and hunting down memory regressions. In times like these the line between software engineer and production engineer became quite blurry. But again, I just found it amazing to work on something so large scale and important and also enjoyed the relative autonomy and responsibility I had. Of course, the less enjoyable part of this release process was the fact that we had to roll back everything multiple times because of some bugs I caused. I wrote around 30,000 lines of code during my internship and made major changes to our codebase, so a little trouble was to be expected. However, I still felt a tad bad and awkward when I found a stupid mistake I had made.

My whale

My whale

Continuing the above thought, I certainly did enjoy a lot of responsibility over my work. In general, interns are treated as equals in almost all respects at Facebook. I got to work on real problems and real systems. I also got to participate in brainstorms and roadmapping, even in other teams. One particularly cool side-story of my internship was that I got invited to the H2 roadmap brainstorming of Facebook’s source control team. I had given a tech talk at Facebook about compilers (LLVM and clang) a few weeks earlier, after which someone from the source control team asked me if I would like to participate in their planning for improvements to Facebook’s codesearch tool given my expertise in code analysis. As a result of that, the hackathon and some other things I did on the side, I ended up with awesome relationships with quite a few engineers outside of my team.

To wrap up my internship, I had to prepare some slides to present my work to my team in London and Menlo Park. In fact, it so happened that a lot of senior leadership from our larger organization had come to London from Menlo Park and Seattle that week, including our director (who is also the 23rd most powerful woman in tech). I also gathered around five other interns and two full time engineers I had become friends with. So I had quite a few fans at my presentation, which made me very happy. As always, I spent 10 times longer than required when making my slides by artfully crafting them in LaTeX instead of PowerPoint. Why make your slides in one hour if you can spend eight hours instead?

Logging Out

Towards the middle of my internship one of the engineers from the source control team I had become friends with, who had been an intern himself, pointed out how insanely fast internships go by. I tried very hard to ignore that statement, but my last day did come. I was very sad, but made a good exit by fixing one last bug in the fading hours of my internship.

And that was it, the twelve weeks of my internship had passed. All I can say is that I not only grew an enormous amount as an engineer, but also as a person. Having such a huge number of smart, helpful and experienced people around me was amazing. On top of that, I had a lot of fun. I really want to thank my team, all the engineers in other teams I worked with and especially my manager for helping me grow and all other interns and friendly faces for making my time so enjoyable. I’m glad there’s social networks like Twitter for us to stay in touch. Or did I miss something?